Legend Story Studios developer Karol lifts the curtain of the Dev Room so we can take a peek behind the scenes. Learn about the work that went into designing, testing, and evolving the iconic cards you know and love today. Sometimes all a card needs to be great is a Dev Touch!

I have previously talked about how some cards never make it through development. Some card concepts just don’t gel – balance issues, it might not be the right time, or the card simply feels too awkward to play. This happens across the entire card spectrum, from common to legendary, and occasionally even to weapons or heroes. It’s normal for hero abilities to go through a series of tweaks and reworks, but every now and then, a hero has such fundamental issues that they get completely pulled from the game.

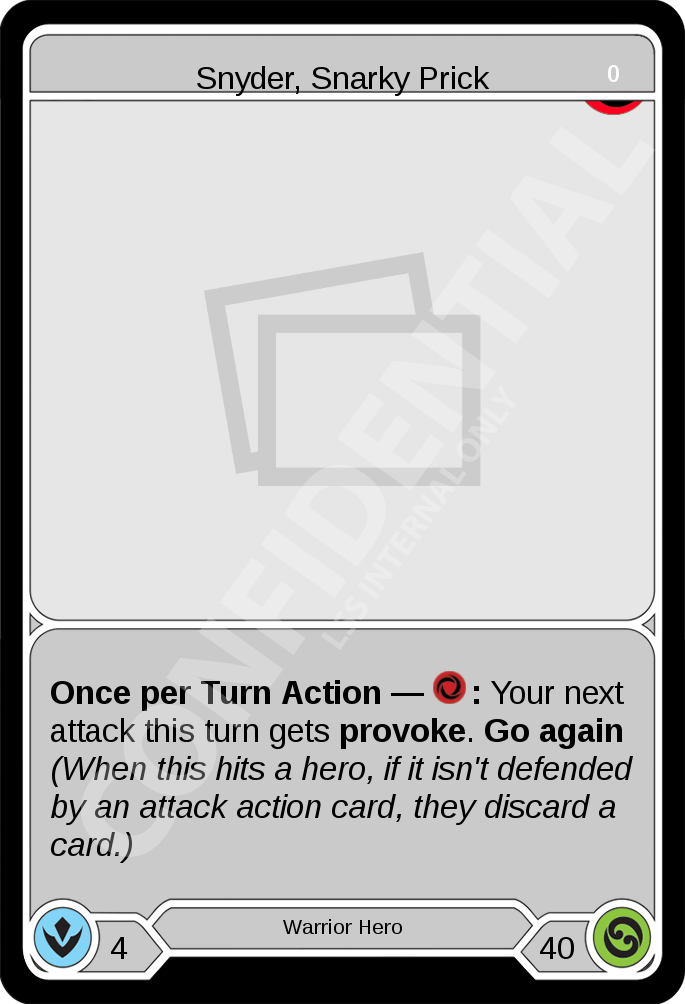

So… let’s talk about the Snyder cut.

Long before Super Slam, the Deathmatch Arena was filled with all sorts of “Reviled” and “Revered” characters. Victor Goldmane fixed matches and stole glory. Kassai fought for Gold to raise an army. Ferocious Kayo looked for new ways to cheat the system. While not explicitly using the Reviled and Revered talents, Heavy Hitters introduced a new breed of morally grey competitors. Not quite heroes, not outright villains. Some were just… pricks. And Snyder was one of them.

Thematically, this was spot-on. Snyder’s ability embodied his provoking nature, forcing opponents into close combat whether they liked it or not. Mechanically, it fit neatly into the Warrior toolkit: it triggered reprise effects and synergized with Heavy Hitters cards like Commanding Performance and Agile Engagement.

There were even some exciting metagame implications as well. Against other Warriors or Wizards – classes that often rely less on attack action cards for defense – Snyder’s ability could be devastatingly effective.

In the beginning of Heavy Hitters development, we found Snyder to be a novel take on the Warrior class. A strong dose of disruption to a class that hasn’t seen many disruptive abilities over the years. However, the more we played with and against him, the more we started to see some serious issues.

Snyder’s ability effectively denied opponents the ability to play with a full 4-card hand for most of the game. His strategy revolved around constant disruption, grinding the opponent down turn by turn. Rather than dynamic duels, Snyder games devolved into slow, attritional slogs.

Pulling the Cord

Halfway through Heavy Hitters development, the team faced a difficult decision. Something was off about Snyder’s gameplay loop. While on the surface the synergies with the Warrior card-pool worked, in practice his hero power overshadowed his entire kit.

Rohan, a Senior Developer, was the person to escalate the situation. His argument was clear:

Every Snyder deck quickly funneled into the same fatigue-oriented plan: force blocks, trim opponents’ resources, and crawl towards victory by pitching a card, provoking, and going up a card in the deck. We couldn’t find ways to tweak him through development.

Snyder’s issues weren’t numerical, they contained a fundamental play pattern problem. Adjusting the cost of his ability didn’t fix it. With activation cost adjustments it would almost always or almost never see usage. There was no healthy middle ground. The gameplay it created – slow, linear, and relentlessly disruptive – simply wasn’t good Flesh and Blood.

After a lengthy discussion, the decision was made. Snyder had to be cut.

Disruption and the Psychology of Loss

The reality is, players don’t like being disrupted. It’s no coincidence that cards like Test of Iron Grip and Truth or Trickery have sparked strong emotional responses, even from players who ultimately won those games.

Why? It comes down to loss aversion – the psychological principle that people feel the pain of loss more strongly than the pleasure of equivalent gain. In Flesh and Blood terms, losing a card from hand feels dramatically worse than your opponent drawing one.

This explains why cards like Scowling Flesh Bag provoke such visceral reactions, while functionally comparable effects like Balance of Justice rarely spark the same frustration. Disruption isn’t inherently bad. In fact, it’s essential for creating tension and interaction, but it must be applied thoughtfully.

A well-timed disruption creates excitement. A Snag that catches an Assassin off guard, or a clutch Sink Below from arsenal against a dominated Guardian swing. These are the moments that make Flesh and Blood thrilling. But when disruption becomes constant, when it strips away the player’s ability to respond or rebuild, it ceases to be engaging. It becomes oppressive.

That was Snyder’s fatal flaw. His disruption wasn’t occasional or strategic, it was the entire experience.

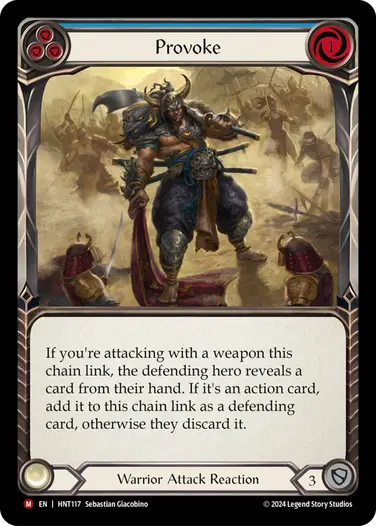

Provoke

The story doesn’t end there, though. From Snyder’s ashes came something lasting, the card Provoke itself.

As a standalone blue resource card, Provoke was introduced as a nod to the Snarky Prick, capturing his spirit without his excesses. At 1-cost, it’s elegant and situational, a small injection of disruption that rewards prediction and skill rather than repetition. It gave Warriors the ability to poke at opponents’ plans without overwhelming them, and in doing so, it fixed the problems that were present in Snyder’s hero ability.

Lessons Learned

Snyder’s journey is a reminder that even failed designs have value. Each misstep teaches us something about balance, theory versus practice, and what makes Flesh and Blood so exciting to play. Snyder taught us that disruption must create tension, not frustration, that control must feel earned, not oppressive – something that is extremely hard to achieve.

And sometimes, a discarded idea just needs to be reshaped, not forgotten. Snyder may never have entered the Deathmatch Arena, but his legacy lives on every time Provoke hits the table – proof that even the pricks of the past can evolve into something better.